Making sense of the Uber ban

Londoners are gearing up to say adios to Uber – or at least they thought they were. It’s not officially going anywhere yet, but the government organization responsible for transport in London has said that the taxi app isn’t “fit and proper” to operate cabs.

Transport for London (TfL) announced last Friday that it wouldn’t renew Uber’s license. It said that Uber isn’t fulfilling its responsibilities as a company (its 'corporate responsibility') – on some basic stuff.

That list included its approach to reporting serious criminal offences, the way it gets hold of information on drivers (like medical and DBS checks) and the fact it uses something called Greyball software, which stops regulators from accessing information from the app.

Almost immediately the company announced it would appeal, and launched a petition that saw hundreds of thousands of people call for it to stay.

But it all de-escalated just about as fast as it escalated – Uber apologised, and Sadiq Khan, the London Mayor, agreed to enter into talks with the company. (Between you and us, we’d be surprised to see it actually go, and if it does go, something else will probably pop up in it’s place…)

But even if this particular drama dies down, the questions it raises about ‘gig economy’ firms that rely on freelance workers to run huge corporations remain. Why does Uber have to be issued a license? Will we have to go back to the pre-cheap cab price? How much should we care about a company’s behavior more than our own pursuit of convenience?

In fact, this whole thing boils down to a few economic issues.

Regulation

So why is it TfL’s place to tell Uber what to do in the first place?

Well, TfL (Transport for London) is run by the government. It’s responsible for making up the rules that companies have to live by in order to operate in TfL’s area. That’s why Uber still exists in other places in the UK – because it’s only TfL’s rules the company’s breaking, not national ones.

Those rules, imposed by government on businesses, are called . The point of regulation is to make sure that all the individuals that make up an economy are acting in a way that is fair, safe, and above-board.

While some people think that businesses should have to operate within a strict framework, others believe that framework slows things down. People talk a lot about ‘red tape’ in business – businesses spend so much time and money making sure they're not breaking any rules, it eats into the time they have to actually produce whatever it is their producing.

People who believe in a 'free market', without regulation, believe that rather than having those rules imposed you should leave it up to customers – the 'market'. If they're not OK with something, they won't buy it, and the company will fail.

Competition

Black cabs vs Uber. Uber vs Lyft. The response to Uber (and the ban) has as much to do with the other cab companies on the road as Uber itself.

Uber launched in London (its first UK city) in 2012. By 2015, it had increased the total number of cabs on London’s roads by 26 per cent to over 62,000 (up from just under 50,000 in 2013).

But the number of minicab companies (with actual physical cab offices, and phone numbers you had to ring to book a car which would turn up in like, 40 minutes… so quaint) declined. In other words, Uber ate them.

And soon the number of Ubers on the road way outstripped the number of black cabs (London’s iconic round taxis). At last count there were 21,000 licensed black cab drivers, there are 40,000 Uber drivers.

When Uber entered the cab market, it had its fancy technology, cheap prices and convenient-ness, and the existing cabs just couldn’t compete.

In fact, one of the black cab drivers’ biggest arguments against Uber was that it had an unfair advantage, because the drivers didn’t have to charge as much as they did, and didn’t have as many regulatory restrictions on them.

Competition is also going to be important if the ban does stick – now consumers are used to that cheap, convenient cab life, something should come into its place. Lyft, for example, has positioned itself as a more ethical Uber, and tends to profit whenever Uber falters. Take the whole #deleteuber thing back in January – in the days after, Lyft (momentarily) overtook Uber in the App Store for the first time ever.

Innovation

But there’s a big counter-argument to that unfair-advantage stuff, which is that Uber beat all those other companies because it’s just better.

Uber, and lots of tech start-ups, position themselves as leaders of innovation. is normally something that’s supported by governments, and the process of developing and implementing new technologies is really important for economies.

But Uber’s business model isn’t just innovative because it’s based on an app – it also was part of a group of companies (Deliveroo, and AirBnb are the most commonly used examples) that completely changed the way people were employed. It’s what’s called the gig economy, and it leads us to the next point, which is...

The 'gig economy'

(See what we did there)

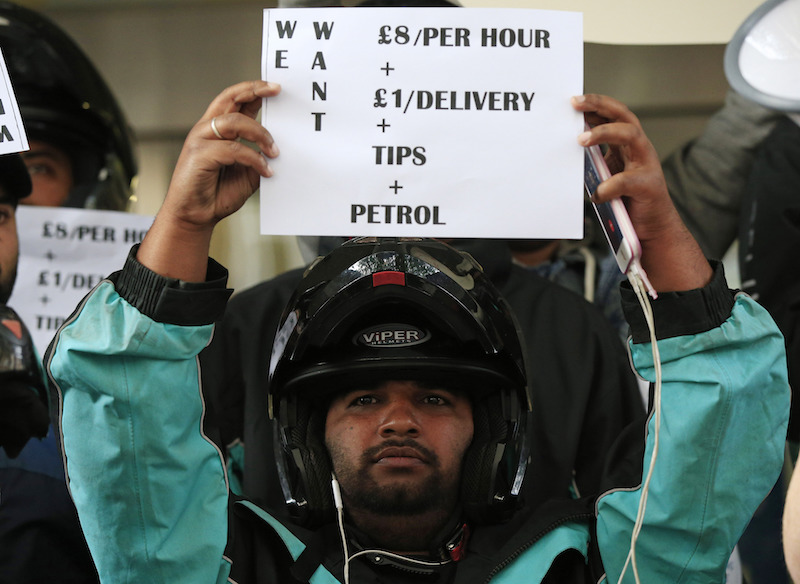

OK, to be completely honest, this one’s a bit misleading. The Uber ban isn’t strictly about its gig-work business model. But most of the public mistrust and controversy around Uber and the gig economy is about the treatment of workers, and it is currently involved in another major tribunal about workers rights.

But the ban is about the way the company, Uber, takes responsibility for the actions of its workers, and that is all tied up in the blurry lines around the gig economy.

The argument, and the basis of Uber’s latest tribunal, is that Uber drivers don’t work for themselves as Uber has claimed, but are employed by Uber. Which means they deserve the same rights as employees (sick pay, holiday pay etc) but it also means (presumably) that the company would have more corporate responsibility.

Consumer choice

Remember #DeleteUber? The company faced its biggest (of many) social media backlashes in January this year. When Donald Trump first announced a ban on people arriving from certain predominantly Muslim countries, there was a big protest outside JFK Airport in New York. New York cabs decided that in support of the protest, they’d stop running cabs from the airport. Uber made its cabs cheaper, to fill the demand. It was estimated that more than 200,000 people deleted their Uber account as a result.

The London Uber ban is only the latest in a series of controversies: arguments about the mistreatment of drivers, the mistreatment of customers, and of its internal staff.

...but how long do consumers really stick to their principles when there’s a cheap and convenient product at stake? This Daily Mash headline kind of sums it up...

Why we make the choices we do as consumers – what to buy, and who to buy it from – is called .

Put simply, it says that you choose to buy the things that give you the greatest satisfaction, while keeping within your budget. Under consumer choice theory, unless your principles ranked really high on your priority list, you’d probably get that Uber.

But, a big area of economics, called (why we behave the way we do), argues against the consumer choice theory. It says that our economic choices are influenced by other, less measurable factors – how you feel about Uber as a company, for example, could mean that you think twice about using the app, no matter how much cheaper, or how much quicker, it can get you home.