As an asylum seeker, I’ve already had many difficult times in my life. Coronavirus won’t stop me achieving my dreams.

This article is part of our Voices of the Economy series. The project brings together the economic experiences and opinions of people from a range of different backgrounds and showcases voices which are not heard as often when we talk about the economy. To find out more and share your own story, click here.

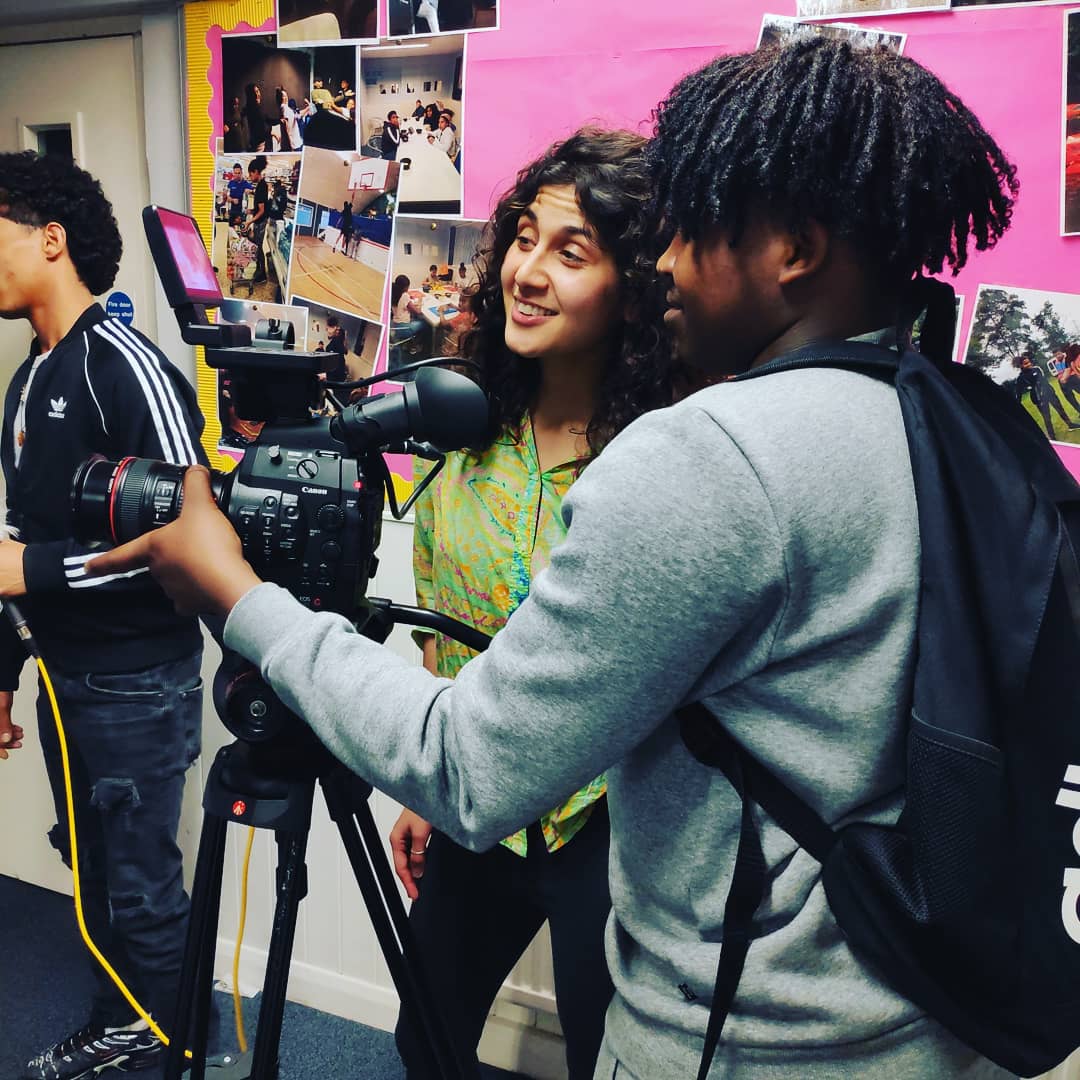

This article was co-written by Jamal, a young asylum seeker, and Mona Bani, co-director of May Project Gardens. May Project Gardens works mostly with unaccompanied minors (children under the age of 18 who arrive in the UK alone). Through their youth programme Hip Hop Garden, they try to understand what being a young asylum seeker or refugee really means; what the lives of these young people are like as a consequence of their legal status and being far from their homes and families.

Migration - the long-term movement of people from one place to another - takes many forms. Two types of migration that are often discussed by politicians and the media are economic migration and refugees.

They are not the same thing. Refugees are forced to move because of direct conflict in their country, like war or persecution, which is life threatening. (While they are waiting for their refugee status to be confirmed by their host country, they’re referred to as asylum seekers.)

Economic migrants aren’t fleeing war or direct persecution, but still feel forced to move to escape challenging economic circumstances which can in many cases also be life threatening. So they migrate to find work and better living conditions than those available to them in their own country.

However, that doesn’t mean that migrants affect the economy and refugees don’t. They do! When refugees move they become part of their local economy - as residents, workers, consumers and community members.

They are more likely than native-born locals to start new businesses, which create jobs and taxable wealth. They bring with them different recipes, music, crafts, languages, stories and other forms of culture.

Someone who knows all of this first hand is Jamal, a Sudenese teenager and asylum seeker who we’ve spent a lot of time with at May Project Gardens.

This is his story.

I’m 17 and I’m an asylum seeker from Sudan. I came to the UK last year, in 2019, by myself. My journey here took three years.

I left Sudan in 2016, when I was only 13 years old, and travelled through Chad, Libya, Italy, France, and Germany until I finally arrived in the UK. I already spoke Arabic, but through my travels I had to learn some Italian, French and German to get by, and now I’m learning English.

You might be wondering why I would leave my home and travel so long to come to this country. I wanted to live somewhere where I’d be free from judgment based on religion or skin colour; somewhere with diversity and a Sudanese community. As Sudan was colonised by Britain until we gained independence in 1956, I had a connection to British culture and therefore felt comfortable to move here.

But what I didn’t expect before arriving in the UK, was how difficult and complicated the asylum process would be. When I first arrived, I was exhausted from the journey. Everything was new to me and I didn’t know anyone. I slept on the street for three days.

I met someone from my country, and I asked him where I could get help. He told me to go to the police and say I’m an illegal migrant. I went to the police station and told them that I was from Sudan and had arrived by myself, without parents. They took my fingerprints and drove me to a foster carer.

I lived with her for two months before being moved to a semi independent house, with four other young people and a key worker who lives on site to supervise us. I got a solicitor to handle my asylum case and told her everything about my experience. She’s written my case and sent it to the Home Office, who decide whether or not I get to stay here. But it’s been eight months and I still haven’t even had my interview for them to assess my case.

Once I have my interview, they’ll decide whether I get to remain in the country or not. Even that part can take months, or even years, for some people to get a response. So I could still be living in limbo, with no certainty for years to come.

It's very stressful to carry all this at 17, on my own. I’ve struggled with sleep deprivation for most of my life because I can’t stop thinking. It makes me feel anxious, helpless, and unsure about my future.

My home country has no safety and is ruled by dictators. People are dying from the wars. The government and Janjaweed are killing people; doesn't matter if they’re children, women, or men. They just kill them. That’s why I left and came to the UK to live in freedom. But I didn’t realise freedom was also so hard to come by here.

I go to college now and I want to be a doctor in the future. I want to help people always. I’ve had many difficult times in my life, so Coronavirus won’t stop me from achieving my dream to become a doctor.

But until I get my status, I’m not allowed to work in the UK, no matter how much I might want to. My life’s not easy but I must get through it.

Would you like to help Jamal and young people like him?

Here at May Project Gardens, we’ve seen first hand how the hostile environment created by our government is brutal for young people like Jamal. We need as much pressure as possible to change it.

Actions you can take include:

- Writing to your MP and publicly holding them to account on these issues

- Attending protests & signing petitions calling for changes to hostile immigration policies

- Offering money, time or skills to frontline, grassroots organisations. Search for projects local to you so you can actually see the work they do.

- Becoming a mentor or tutor to a young refugee / asylum seeker

- Offering housing through organisations like Refugees at Home

- Donating to ethical funders like Help Refugees

- Becoming a foster carer

If you want to support our holistic programme of creative workshops, food, English language, paid work experience, residential trips, community garden sessions, mentoring and crucial community building, go to www.mayproject.org